“Creativity is not a talent. It is a way of operating.”

– John Cleese –

At the dawning of the age of automation, there’s a certain irony to the Monty Python star’s comments.

While the discussion about the age of automation and future of work rages on in a shroud of uncertainty, and even fear, there are some whose roles defining and creating the future have led them to confront a more abstract question: how will augmentative technology impact the creative process?

Are the innovator, the artist, and the entrepreneur facing the same threat of redundancy as so many other professionals?

The answer – in stark contrast to cries of “a robot stole my job!” – is highly optimistic, and offers exciting insight into the potential of digital intelligence.

Rather than replace the need for human creativity, such technology will instead be developed to amplify it. For those willing to embrace it, digital intelligence will become a creative collaborator.

The muse in the machine.

Early exploration of this relationship has given rise to a process called generative design, which pairs human intuition with the tech’s ability to explore potential in a logical manner.

You might think of it like evolution: the human defines the environment in which an idea will flourish or die, while the machine calculates ways to ensure the former comes to pass.

We’re already seeing simple, yet stunning examples of generative design at play. Researchers Neill Campbell of University College London and Jan Kautz of NVIDIA Research looked to democratise the process of creating fonts – a role currently performed by highly specialised professionals who have traditionally required many years of training to reach the echelon of design artistry – in a project entitled Learning a Manifold of Fonts.

By injecting 1000 fonts into a generative manifold they named the Gaussian Project Latent Variable Model (GP-LVM), Campbell and Kautz produced an interactive 2D tool that allows users to explore a font family’s variations all with a drag of the mouse.

“This unsupervised learning process requires no input from either an end user or a professional typographer and yet is capable of generating new, high quality fonts,” the researchers explain. It’s all thanks to the tech’s ability to use what already exists to hypothesise what could exist, but doesn’t, ultimately leaving the human to decide what option they would like to pursue.

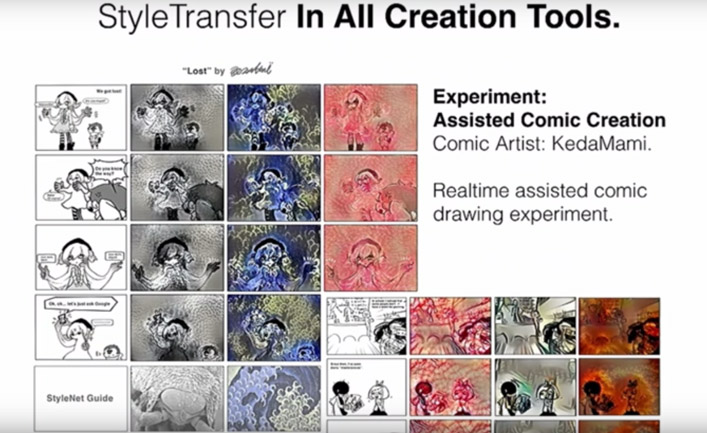

Above is another example, this time from Creative.ai co-founder Samim A. Winger’s presentation on generative design. This tool has been created to assist in the stylising of a comic book by applying elements of reference images to the artist’s completed panels.

Instantaneously, the tool can present a range of automated stylistic possibilities to the artist.

Of course, these are rudimentary examples.

So what will this technology be capable of once it is fully developed.

In his TedxPortland presentation (viewable below), futurist Maurice Conti shares one example:

You sit down in front of your computer, and tell your artificial intelligence partner to build you a car. It presents you with a basic template. You tell it to change the shape – perhaps to make it more Japanese rather than European in design – and that you want an automatic transmission. You keep going, making changes by voice rather than by hand, and seeing your instructions followed on the screen in real time.

When you’re done, your screen displays a car created not with a mouse and keyboard, but with your mind.

And there’s potential to go even further than that!

You might simply tell the system to create what it believes to be the optimal car. In response, it will design a vehicle that no human could ever make, one free from such artificial restraints as aesthetics, or traditional geometric make up.

Here, perhaps, is the most important point of all.

The key to making the most of this technology will be treating augmentative systems as peers rather than tools. We must be willing to admit that machines will be able to design in ways that we can never imagine, and that this is a positive step to utilising all of our creative ability.

For more on generative design, check out Conti’s speech, The Incredible Inventions of Intuitive AI below. He discusses creation as a method through which people can be given exactly what they want (a definition that, I believe, does some disservice to the exploratory element of the creative process, but is no doubt worth considering), offering some fascinating insight into design on a much larger scale than a single human mind.

I’m very interested in the whole debate about artificial intelligence and I agree with you on the fact it shouldn’t be feared per se or be dealt with preconceptions.

What I can’t completely agree on is why manual work and more in general any activity that is not purely brain activity but rather involves the use of our body has to be seen as a limitation or, even worse, as something to get rid of. Human beings are not merely brains. We do have a body and that body is not useless.

Actually it is rather the opposite: most of our more meaningful interactions with the surrounding world and with other human beings wouldn’t be possible without a body.

Manual work may be and is in fact gratifying for many. Drawing and painting by hand, gardening, riding a bicycle, playing an instrument, cooking and so forth may be extremely rewarding and satisfying.

Older generations experienced how different are “real” relationships compared to social media “friends”.

And what about handwriting? A 2008 study published in the Journal of Cognitive Science shows how motor stimuli can influence our visual recognition and suggests that engaging the motor nerves to create shapes by hand helped cement the ability to identify such shapes.

Also we should take into account that technology is changing way faster than human evolution. We are still substantially very similar to our ancestors (homo sapiens) who lived 200,000 years ago. This to say that we are not able to adapt as quickly as we wish to.

I appreciate the comment, Paolo.

I understand where you are coming from, though I would argue that what you are talking about is a side effect of artificial intelligence, rather than the justification for it.

As we see with generative design, the system works as a supportive tool. It does not replace the artist, it instead enables them in ways our brains are not capable of.

Of course, there are systems being designed to replace humans in the workforce altogether, but they’re not solely targeted at blue collar or other physical jobs. Professions such as accountancy and law – those that rely almost purely on brain power – are being made redundant at the same pace, merely because machines have the capability to exceed the limits of human potential.

I’m sure it will still be possible for people to tend to cook in their own kitchen, or balance their taxes if they wish to do so after automation is the norm. It will only be their ability to make a career out of doing so that will prove challenging.