An obsessive need to fulfill a singular purpose. A purpose that has been with us since our youth. A purpose that has come to define our very existence.

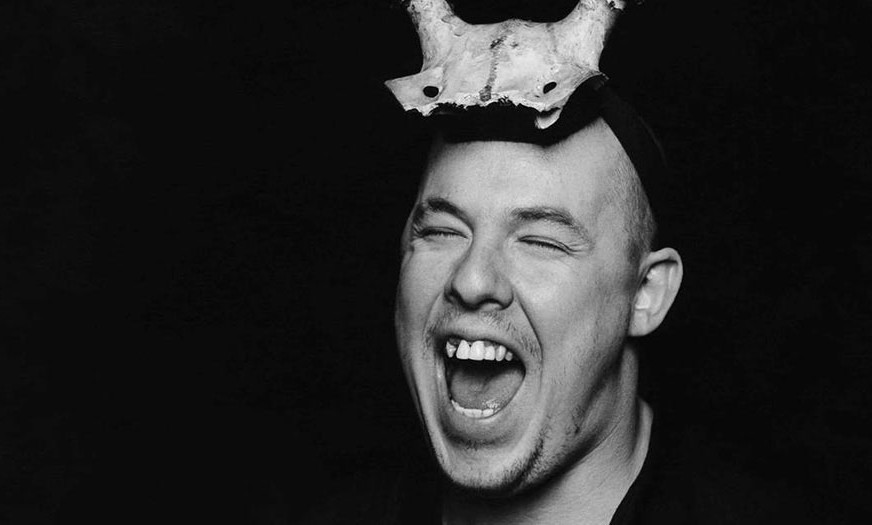

It’s a feeling many of us can associate with, but few will ever experience quite as intensely as the brilliant, confrontational fashion designer Alexander McQueen did. In the new documentary about his life, simply entitled McQueen, his compulsion to create is laid bare by family, colleagues, and mentors. And though it’s mostly a celebration of McQueen’s passion and impact on the industry, what lurks beneath is a potent warning about the danger that comes with throwing oneself ravenously into the pursuit of a single goal. It’s this subtext that elevates the film beyond the many other fashion films released this year.

McQueen doesn’t need to establish much to prove its subject was a man who existed far outside the realm from which the great designers of the past have sprung. The youngest of six children in a working class family from Stratford, London, McQueen was chubby and unkempt. He disliked the industry. He disliked the aesthetic. But there was no denying his potential for greatness. Several times throughout the documentary, former teachers and employers of McQueen are quick to point out that they did not teach him his talent, but merely provided him an outlet through which to hone it.

While it was his technical skill that gave McQueen his break, it was his unique style and tone that made him stand out. In archival footage, McQueen calls his work “confessional”, and as the film moves through its five chapters, or ‘tapes’ – each culminating in one of the artist’s most definitive shows – it reveals the extent to which his views and anxieties informed his bold design choices. From his highly controversial reflection on the pillaging of his ancestral land in Highland Rape, to the bright and bold presentation of his first show for Givenchy, The Search for the Golden Fleece, McQueen offers incredible insight into the designer’s process.

Whatever choices he made, the film explains, they were made with integrity and the desire to move an audience, not to make headlines. In fact, for most of the 111 minute run time, he seems completely uninterested in personal attention. McQueen felt much of the industry and the media didn’t believe that to be true (when he instructs a model to “go put your pubic hair in Ana Wintour’s face” it’s easy to see why), but he didn’t care. He believed in the work, and the work was all that mattered.

That truth would eventually lead to his downfall, embodied in director Ian Bonhôte and co-director Peter Ettedgui’s delicate use of the McQueen skull motif to chronicle both the violent beauty of his work, and the constant battles he fought to persevere.

At the peak of his career, McQueen took on the monumental task of staging 14 shows a year. As passionate as he remained, his success was taking its toll, as Bonhôte and Ettedgui explore in detail. Interviews with former McQueen designer Sebastian Pons prove the most enlightening, and disturbing, as he delves into his friend’s drug use, regret over his liposuction, and suicidal ideation – at one point revealing McQueen considered shooting himself at the end of one of his shows.

In 2010, McQueen expressed a growing disinterest in his work. It was not that his career had stalled – he’d recently made the move from Givenchy to Gucci, and was being celebrated the world over – but he was no longer inspired to create.

That, more than any of the other many reasons, feels like what ultimately led Alexander McQueen to take his own life later that year.

So while McQueen is a sombre celebration of a brilliant artist, it’s cautionary tale of a man who gave everything he had to his work, only to be left feeling empty when he realised it didn’t bring him the satisfaction it once did, is one that should not be understated. Through his art he fought his demons, and without it he could never hope to stand triumphant.