Funai Electric are the last Japanese manufacturer of VCRs, and in August 2016, their production lines will grind to a halt.

The move marks an end to 33 years of production at the company, and the swansong for the device, which has been a standard for households and a range of businesses alike for six decades.

In honour of this momentous occasion, let us rewind the history of the VCR – the machine that defined home entertainment for so many – and share in the journey.

We promise it won’t take as long as actually rewinding a VHS did back in the day.

—

It all started in 1956 with videotape recorders – VTR. The Ampex VRX-1000 launched with a $50,000 USD price tag – around $450,000 USD in 2016 – making it affordable only for the largest media broadcasters. Add to that the machine’s considerable size, and the task of selling the VRX-1000 could seem quite a challenging one. Yet it had one thing going for it: quality. And quality was just what the market needed.

In a few short years, the technology had expanded into the fields of medicine, aviation, and education, creating a new standard for video production.

With this expansion came technological advancements, and by 1963 the VTR was ready to enter the home.

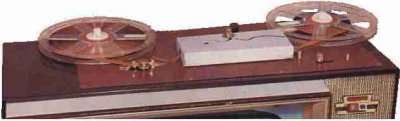

In England, the UK Nottingham Electronic Valve Company began to sell the Telcan. A cultural marvel, the unit could be purchased for £60 (around $1600 USD) and featured reel-to-reel recording of television programs. There was a catch though: the Telcan could only record for 20 minutes at a time, and this would eventually lead to its redundancy. Only two are left in existence today.

It was the Japanese who would end up counteracting this issue. Toshiba, Philips and Sony had all been experimenting with VTR, but it was the latter’s CV-2000, which released in 1965, that would be the most successful. It could record up to an hour of content, was almost half the price of the Telcan, and was designed with average users in mind, rather than the early adopters and tech heads who had bought the older device.

Meanwhile, home audio and video recording devices were being replaced by those using cassettes. Within a four year period, Stereo-Pak, audio cassettes, Instamatic film, 8-tracks and Super 8 film all came into existence, redefining the entire industry.

Most important of all was the introduction of movies onto video cassette in 1967. In that moment, modern home entertainment came into existence.

Sony would continue to lead innovation in VTR medium for the rest of the decade. The U-matic prototype was first shown off in October 1969, and would become an industry standard in 1971. A larger version of the VHS cassettes that would become the norm in later years, it could record up to 80 minutes. The machines produced to record on U-matic were widely used by businesses, but was too costly for the average home at $1395 USD.

The hole left in the consumer market would be filled the following year by Sony’s competitor, Philips. Their N1500 was the first true VCR player, and though price was once again an issue for most homes, later updates to the machine would turn it into a common household item.

By 1975, VCR had gained traction, and six companies entered battle to bring their products to the most homes: RCA, JVC, Ampex, Panasonic, Sony, and Toshiba. Three incompatible technical standards were borne during this competition in order to cordon off sectors of the market.

The two most important of these standards were JVC’s VHS and Sony’s Betamax. VHS had tape duration on its side; Betamax, overall quality. The so-called videotape format wars unfolded over the next six years, and left VHS the clear winner.

Consumers had spoken: convenience came before quality.

In 1980, less than 1% of American homes had VCRs in their living rooms. By 1987, 50%. Projections showed that by 1990, 90% of Americans owned a VCR.

Over this period, Universal Studios took Sony to court, arguing that the machine broke copyright violations. Motion Picture Association of America head Jack Valenti warned of the “savagery and the ravages of this machine” to Congress. And yet it prevailed, setting a precedent for consumer rights that holds firm today.

In January of 2002, DVD sales surpassed those of VHS, but the decline of the medium was slow. VCRs were still popular with those who had extensive movie collections, and were able to be sold considerably cheaper in countries like China which had restricted the importing of foreign goods for many years prior.

Even now, as Funai Electric bring an end to VCR production, it seems like the medium will carry on for some time. After all, Sony stopped making Betamax recorders in 2002, but continued making tapes for 13 years after, and at their peak they had only been selling to 25% of the VCR market.

**This article is now over.**

**Please be sure to rewind it for the next reader.**