The stories of great minds who slept a mere hour or two each day while delivering to the world some of its most important ideas, artworks, and inventions, are the stuff of legend.

And, like most legends, they are entirely exaggerated.

It started with the myth of how Leonardo da Vinci worked 22 hour days throughout his life, but perhaps the modern notion that sleeping interferes with a person’s industrious and creative endeavours derives from Thomas Edison’s pointed declaration that “Sleep is a criminal waste of time, inherited from our cave days”.

From this statement, rumour abounded throughout the press and in the streets, culminating in a cult-like mindset held by those who think the best way to find success is to emulate the lives of successful people. It’s a theory that pervades even the present day, and one that does more harm than good.

For Edison’s words were just dialogue in a show designed to make him appear an inhumanly hard worker.

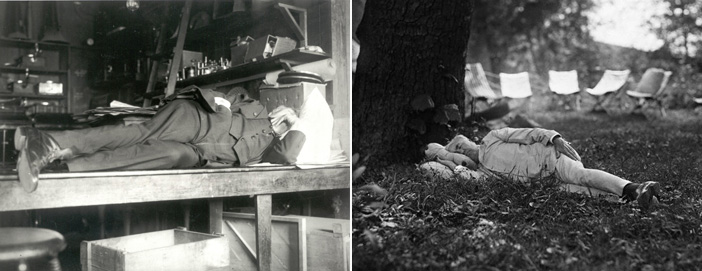

He actually slept a lot more than he let on.

Yes, sometimes he wouldn’t sleep for a long spell…but then he’d sleep for an entire day in an attempt to make up for it.

It was the same for Isaac Newton, who did not so much sleep as nap – a fact that may have lead to the tall tale of how he began to put together the theory of gravity. Newton’s rejection of sleep lead to sickness from exhaustion, and was a major contributing factor in his eventual nervous breakdown.

Essentially, the sleep patterns of the likes of Edison and Newton were the result of framing a public image of themselves, and an ignorance of the modern neuroscience that provides the kind of data that has clarified the importance of sleep in a healthy lifecycle.

On average, a human sleeps 8 hours a day – around one-third of their entire life is spent recuperating from the other two-thirds. Some see this as a point of laziness – Edison compared it to overeating, believing that it resulted in the same kind of ineffectiveness – but in truth it is critical to prolonged success.

A 1961 study entitled Interaction of Lack of Sleep with Knowledge of Results, Repeated Testing, and Individual Differences found that repeatedly restricting test subjects from a night’s sleep had a cumulative effect on those involved. Dubbed sleep debt, the research highlights how difficult it can be for individuals to recover from even one sleepless night, especially as they grow older.

In contrast to the brilliant thinkers who discredited the value of sleep are the ones who embraced it.

Einstein had 10 hours of sleep every night, unless he was working on something that was keeping him incredibly busy. In that case, he slept 11, as he said that his dreams helped him to invent and solve problems.

Winston Churchill only slept around five hours a night, but took a nap of one-and-a-half to two hours each day.

“You must sleep sometime between lunch and dinner, and no halfway measures. Take off your clothes and get into bed. That’s what I always do. Don’t think you will be doing less work because you sleep during the day. That’s a foolish notion held by people who have no imaginations. You will be able to accomplish more. You get two days in one – well, at least one and a half.”

And what was the first thing US President Calvin Coolidge did when he entered the White House? Take a nap.

The type of sleep exhibited by Churchill and Coolidge is called polyphasic sleep, and was first defined by psychologist J. S. Szymanski in the early 1900s. Polyphasic sleepers divide their sleep schedule into multiple parts of the day in order to help their brains stay focused. Edison and Newton did this too, but to such an extent that perhaps the only thing they were doing was depriving themselves of sleep.

The more extreme value of sleep can be found in Salvador Dali’s hypnagogic naps – better known as microsleeps.

Dali’s process was called ‘Slumber with a key’, and was designed to allow him a nap lasting only a single second.

He would sit in his chair, arms on armrests with his wrists dangling over them. A heavy metal key was grasped between his thumb and forefinger, suspended over an upside-down plate that sat on the floor.

As soon as Dali dozed off, the key fell from his hand, strike the plate, and the resulting noise would startle him from his slumber. In that moment between awake and asleep, Dali found himself “in equilibrium on the taut and invisible wire that separates sleep from waking”, and there he found the muse that revived both mind and body.

Of course, he also made a point of getting a good night’s rest.

So there it is. The science and testaments of brilliant individuals prove that a lack of sleep is not something to wear proudly like a badge of honour. If anything, it’s hurting those who try.

Next time someone tells you “early to bed, early to rise, makes a person healthy, wealthy, and wise,” you can remind them that’s very much not the case.