Switzerland, 1886: Victor Hugo instigates the Berne Convention, designed to protect droit d’auteur (the right of the author) internationally, in stark contrast with traditional copyright law that dealt solely with protection of a written piece in its country of origin.

It set two major precedents. First, it ensured writers would receive fair compensation for the publication of their work around the world. This was a huge issue at the time, considering countries like the Netherlands where the printing industry was established around the sale of translated books not protected by copyright.

Secondly, the treaty required signatories to enforce copyright protection for the duration of a writer’s life, plus another 50 years.

When that period expired, the work transitioned into the public domain, and belongs not to the writer, but to everyone. It’s why we now have content like the Sherlock Holmes television series, ‘expanded universe’ media like Ron Howard’s In the Heart of the Sea, and most of the classic Disney flicks that we watched as children.

Yes, Disney. The Little Mermaid. Cinderella. Sleeping Beauty. All stories and characters derived from writing that entered the public domain years before Walt Disney Studios was established.

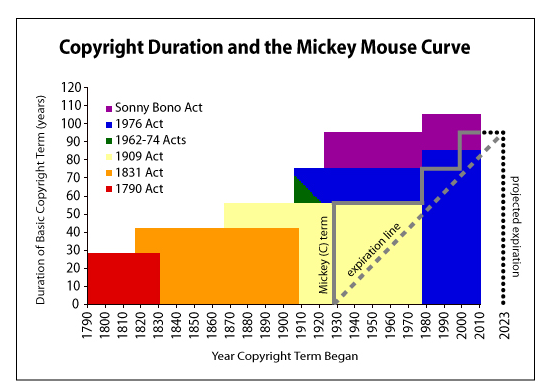

The US refused to sign the Berne treaty because of the impact it would have on the country’s pre-existing copyright laws, but by the time Walt first drew Mickey Mouse in 1928, the little rodent with the red shorts would be covered by copyright for 56 years.

That meant that in 1984, Mickey Mouse was set to enter the public domain, and that made Disney very nervous. He was a more recognisable character worldwide than Santa, and was responsible for a huge percentage of Disney’s revenue (in 2004, Forbes estimated his value at $5.8 billion). They weren’t going to let him go.

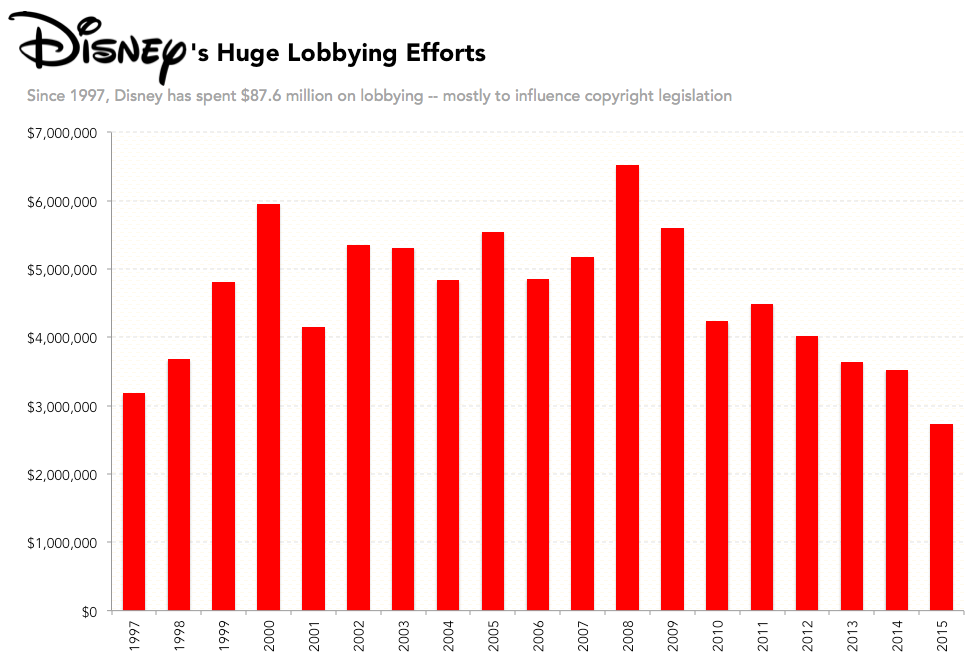

So Disney started lobbying for extended copyright protection. In 1976, they were successful, and the term for which protection was enacted expanded to 50 years after the creator’s death; aligning with the Berne treaty.

But it was the change to copyright covering the work of corporations that was most impactful. Applied retroactively, the maximum term was lengthened to 75 years, meaning Mickey wouldn’t become property of the public domain until 2003.

In the decades that followed, the creative landscape at Disney changed. Original titles like The Lion King were the new norm, while the acquisition of companies like Miramax saw the brand grow in ways previously unheard of. Mickey was still synonymous with Disney, of course, but he wasn’t as big as he once was. It seemed like, finally, he would enter the public domain.

But it was not to be. Disney lobbied the federal government once again, resulting in the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998. Individual copyright protection expanded to 70 years after the author’s death, and corporate works to 95 years from publication, or 120 years from creation, whichever came first. That meant Disney owned Mickey to at least 2023.

The Mickey Mouse Curve charts the change in copyright law with the period under which the character is protected under it. It’s pretty understandable why critics of the change labelled it the ‘Mickey Mouse Protection Act’.

You may be asking why this matters. Well, of course, the act does not only cover Mickey Mouse, but scores of other classic works in desperate need of reinvigoration and modernisation.

Public domain material has always been a hotbed for creative inspiration. Hell, the stories for over 50 of Disney’s own films were derived from it.

That a company would impede future generations of artists from appropriating similar stories is as offensive as the theft the Berne treaty was created to prevent. And if you thought it couldn’t get much worse, you are wrong.

Congresswoman Mary Bono – for whose husband the act was named – stated on the Congressional Record: “Actually, Sonny wanted the term of copyright protection to last forever. I am informed by staff that such a change would violate the Constitution. … As you know, there is also (former MPAA president) Jack Valenti’s proposal for term to last forever less one day. Perhaps the Committee may look at that next Congress.”

It’s not a reality yet, but the possibility should surely concern us all.

What are your thoughts on the issue? Let us know in the comments below.