What Walt Disney was to animation, Theodor Seuss Geisel – Dr. Seuss, as he’s best known – was to literature.

For nearly 80 years, his poetic meter and distinctive illustrations have entertained children in over 20 different languages, and is constantly employed to reaffirm the value of reading both to and for children.

But there was more to the man than his rhythm.

DRAWING INSPIRATION

Seuss’s love of art was instilled in him from birth. His mother (who Seuss jokingly referred to as his “accomplice in crime”) would often send he and his siblings to sleep by chanting rhymes, and encouraged Seuss to draw cartoon animals on the walls of his room.

He spent his early life in Springfield, Massachusetts, a town that would become the breeding ground of some of his most famous work. His first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, was named after a street near which he had lived, and even featured a character that closely resembled the mayor.

Seuss was a cheerful child, and both his parents were eager to foster his creative personality. Even when the family’s prestigious brewing company was shut down at the outset of the prohibition era, they persevered for the sake of the children.

After graduating from Springfield High School, where he had taken his first art lessons, Seuss enrolled at New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College. There, he established a small but close group of friends who would become his lifelong confidants.

The highlight of his time at Dartmouth was his stint in the role of editor at the school’s comedy magazine: The Jack-O-Lantern. His time as editor was cut short, however, when Seuss and friends were caught drinking gin: an illegal act under prohibition. Unwilling to give up writing for the publication, he continued to submit contributions under the name Seuss, adding the Dr. prefix some years later.

A German name, Seuss was often pronounced incorrectly, until Jack-O-Lantern writer came up with a poem to clear up confusion:

“You’re wrong as the deuce

And you shouldn’t rejoice

If you’re calling him Seuss.

He pronounces it Soice.”

As his fame rose, Seuss would adopt the Americanised pronunciation of his name in order to make it easier for children to say.

STARTING A CAREER

Upon graduation, Seuss travelled to the UK, where he enrolled at Oxford in order to become an English teacher at the behest of his father. There, he quickly became bored. It wasn’t long though before he met his future wife, Helen Palmer, who convinced him to give up his academic pursuits in order to pursue a career in drawing.

He returned home, and spent the next four months fanatically drawing cartoons and submitting them to magazines across the world. He tried his luck in New York, but initially failed, telling a friend ““I have tramped all over this bloody town and been tossed out of Boni & Liveright, Harcourt Brace, Paramount Pictures, Metro Goldwyn, three advertising agencies, Life, Judge and three public conveniences.”

In July of 1927, he sold his first cartoon for $25, a sale that allowed him to leave Springfield and move to New York permanently.

In the same year, he was hired as a full-time writer and illustrator for Judge magazine, and married Palmer.

While in New York, his father, as superintendent of parks, had the Springfield zoo send tusks, horns, and bills to Seuss’s apartment, where he used them as the basis for surreal taxidermy sculptures.

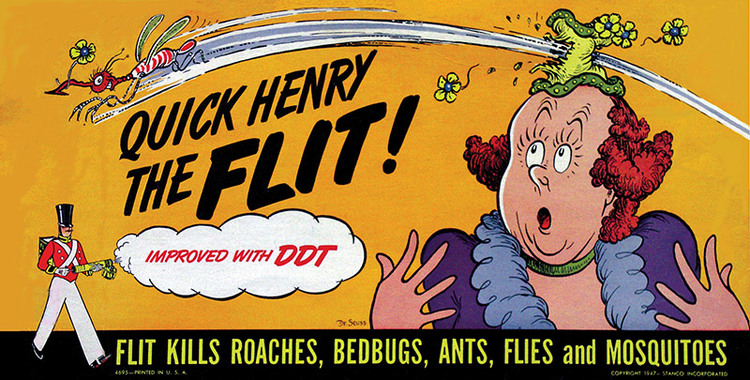

Early in 1928, Seuss mentioned the name of a well-known bug spray in one of his cartoons. Seeing it, the wife of the company’s advertising branch convinced her husband to sign him. Seuss’s subsequent work became the basis of a campaign that ran intermittently for 13 years, and saw him become a popular figure in the industry. Over the year and beyond, his work would be commissioned by the likes of Vanity Fair and Life magazine.

SHIFT IN PERSPECTIVE

After a decade in the advertising business, Seuss began to write children’s books. His inspiration for And to Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street came from, of all places, the rhythm of a boat’s motor as he returned from a European vacation.

A perfectionist, Seuss laboured over the book for six months, before being rejected by at least 20 publishers. It was only through an old classmate that he was finally able to be published through Vanguard Press. Critics loved the book, but sales were less than impressive.

The next four books came over a two year period, as Seuss worked to establish his writing style. The last of these was Horton Hatches the Egg, featuring the titular elephant who would one day become one of Seuss’s most iconic characters.

“Be who you are and say what you feel, because those who mind don’t matter and those who matter don’t mind.”

A seven year hiatus followed, as Seuss turned his attention to political cartoons at the eruption of World War II. He had strong ideals, denouncing racism while concurrently branding all Japanese-Americans as traitors. He then joined the Army as a captain, writing propaganda scripts for Frank Capra’s wartime documentary unit. During this time, he was sent off to witness fighting in a ‘quiet sector’ of France. That night, the Battle of the Bulge unfolded around him. Seuss was stuck miles behind enemy lines until being rescued by British forces after three days.

RETURN TO THE ARTS

Following the war, Seuss began writing for children once more. His books were not derived around a moral (“kids can see a moral coming a mile off”), but were often structured to confront social issues. The best examples include Horton Hears a Who, an allegory for the Hiroshima bombing and a kind of apology for his previously brutal views on Japanese-Americans, and The Lorax, which deals with environmental conservation.

Undoubtedly his most significant books were The Cat in the Hat and The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, both published in 1953. The books are credited for redefining how children learnt to read, and the release of the former was even listed in U.S. News & World Report‘s 2007 issue as one of the ten defining moments that saw 1957 become ‘The Year That Changed America’.

“Greece had Zeus—America has Seuss,” opened the article.

Seuss’s work went on to win many accolades, including an Honorary Degree from Dartmouth, a Pulitzer Prize, Academy Awards, Emmy Awards, and he even received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

LATER YEARS

In 1967, Helen Palmer Geisel committed suicide after a long struggle with illness. “I didn’t know whether to kill myself, burn the house down, or just go away and get lost,” Seuss said in the wake of her death.

He went on to marry his close friend, Audrey Stone Dimond, the following year. When asked why he had not had any children during either of his marriages, he quipped “You have ’em; I’ll entertain ’em.”

Over the following decades, he would complete the second half of his 40-book legacy, including stories such as I Can Read with My Eyes Shut! and Oh, The Places You’ll Go! in which he confronts themes of death only a year before his demise.

Dr. Seuss died of oral cancer in 1991, at the age of 87.

Theodor Seuss Geisel sold 220 million copies of his books during his lifetime, and another 480 million in the quarter-century since. He left us as the most important writer of children’s books ever, and few would argue that he doesn’t remain so to this day. In fact, his latest posthumous release, Which Pet Should I Get?, debuted at #1 on Amazon’s best sellers list in 2015.