David Ogilvy was a magician.

Not in the fantastical, grandiose sense, of course; but as an ad man his skill was in performing right under the audience’s nose so directly, and yet so subtly that they never even realised it.

Today, we know his greatest trick as native advertising, but there were a lot more brilliant ideas tucked up his wizardly sleeves that would, when revealed, come to permanently revolutionise the advertising industry.

—

David Ogilvy was born on the 23rd of June, 1911, in the English city of Surrey. In the 1920s, his family was hit hard by the Great Depression. Ogilvy was only able to continue his education at St Cyprian’s preparatory school when administrators agreed that the family pay reduced fees. Fortunately, his studious endeavours at the school culminated in a scholarship at Fettes College in his father’s homeland of Scotland.

Upon graduation in 1929, Ogilvy received another scholarship, this time to study history at Christ Church, Oxford. He only completed half of his degree, however, deciding instead to travel to Paris in order to apprentice as a chef at the Hotel Majestic. He credits his time here as an experience that taught him discipline and management skills, as well as when to move on. “If I stayed at the Majestic I would have faced years of slave wages, fiendish pressure, and perpetual exhaustion.”

Ogilvy returned to Scotland, where he began selling AGA cooking stoves door-to-door. He immediately showed a knack for being able to sell the product to anyone and everyone, a feat which captured the attention of his employer, who charged him with producing an instruction manual for his peers. The Theory and Practice of Selling the AGA Cooker was distributed in 1935. Three decades later, Fortune would call it the finest sales instruction manual ever written.

Amongst its finest notions was a simple piece of advice which came to change the perception of the salesperson: “The more prospects you talk to, the more sales you expose yourself to, the more orders you will get. But never mistake quantity of calls for quality of salesmanship”.

When he saw a copy of the manual, Ogilvy’s older brother, Francis, took it to his bosses at advertising agency Mather & Crowther. Immediately, they offered Ogilvy a position as an account executive, which he happily accepted.

It wasn’t long before he was flexing his creativity and ingenuity. One story tells of how a hotel owner walked into the agency with $500 to promote the inauguration of his new premises. Such a pitiful budget meant he was palmed off to the newcomer, Ogilvy, who ended up taking the money and using it to send postcards advertising the hotel to people in the telephone directory. The hotel opened with a full house. “I had tasted blood,” he would later recall.

In 1938, Ogilvy convinced Mather & Crowther to send him to the United States for experience. He worked at the Audience Research Institute of New Jersey under George Gallup, who would become one of Ogilvy’s greatest influences. He championed the importance of meticulous research and an adherence to reality that would found the basis of Ogilvy’s future work.

When World War II broke out the following year, Ogilvy went to work for the British Intelligence Service at the British embassy in Washington, DC. He put the Gallup technique to use for the first time in his role, using his knowledge to analyse and make recommendations on matters of diplomacy and security. Specifically, his job was to discredit businessmen who were supporting the Nazi war effort. The report on his work would later be read by Eisenhower’s Psychological Warfare Board, who applied his theories in Europe during the final year of the war.

Following the war, Ogilvy bought a farm in Pennsylvania, living amongst the Amish in an atmosphere of “serenity, abundance, and contentment”. It wasn’t long though before he grew bored, and relocated to Manhattan to return to the advertising game in 1948.

Having never written ad copy in his life, Ogilvy talked Mather & Crowther (at the time being run by his brother Francis) into backing his new agency: Ogilvy, Benson, and Mather (OBM). He started the agency with $6000 (just less than $60,000 in 2016 USD) to his name.

The agency was founded on the principal that the function of advertising is to sell, and that selling relied on an understanding of the consumer. He disliked the patronising tone that ran through so many major campaigns at the time, and detested the idea that customers were any less intelligent than the people selling to them. “The customer is not a moron, she’s your wife.”

After initial struggles to connect with clients, the agency quickly gathered steam. One of Ogilvy’s most important campaigns was for Irish beer brand Guinness in 1950. As he travelled home to Connecticut by train, a thought struck him. He leapt from the train at the next station, and called his office. “You won’t believe this; I’ve had an idea.”

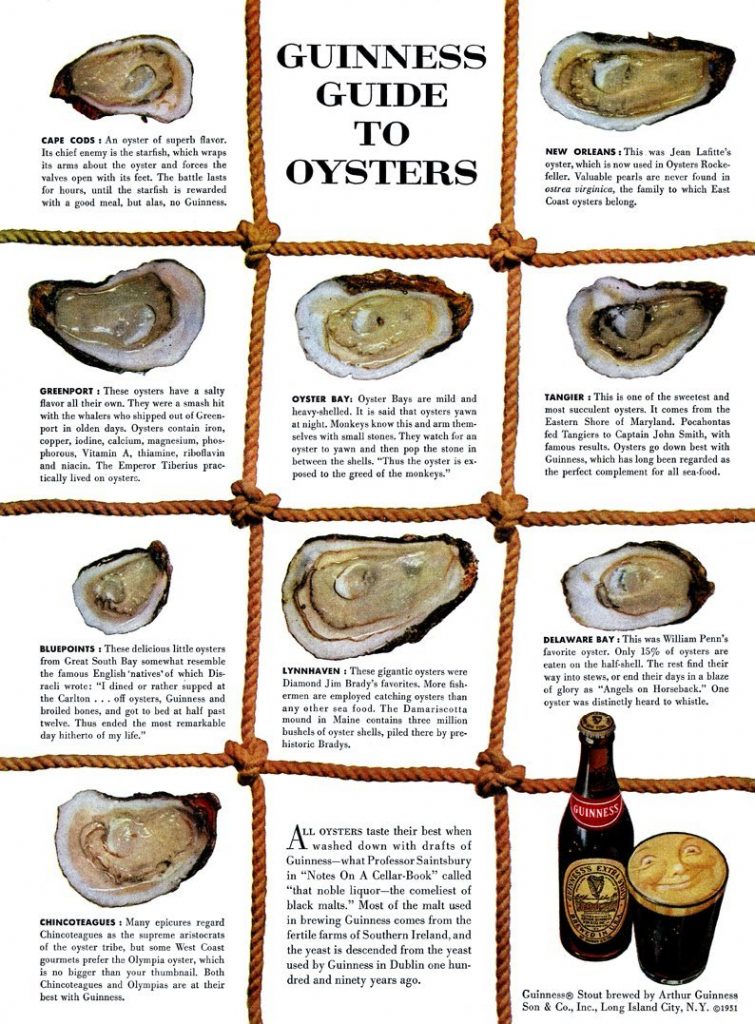

That idea, conceived as The Guinness Guide to Oysters, was a deceptively simple one: highlighting the fascinating foods that drinkers of the stout often ate while indulging in a brew.

It’s link to the advertised product was subtle – the description of the oysters read more like little stories than ad copy – so consumers barely noticed that they were being sold to. It was a major success, and would later be followed up with posters featuring the Guinness guide to cheese and game birds, as well as other foods. The concept would establish what later became known as native advertising, in which ads are placed in the context of the platform or medium in which they are released, rather than traditional, more overt campaigns.

Over the next two decades, Ogilvy cemented his position amongst the titans of the industry by winning rights to several major campaigns from General Foods, American Express, Shell, and Rolls-Royce, along with others. “”I doubt whether any copywriter has ever had so many winners in such a short period of time,” he wrote in his autobiography, Ogilvy on Advertising. “They made Ogilvy & Mather so hot that getting clients was like shooting fish in a barrel.”

Everything Ogilvy touched turned to gold. The Hathaway Man increased sales by 160% for Hathaway Shirts, an obscure company with a history spanning over a century. “Dove is one-quarter moisturising cream” was a promoted fact that helped Dove soap make a profit in its first year of business.

Ogilvy’s proudest achievement came in 1953, with an ad for the Puerto Rico tourism board. Tourist expenditure almost tripled thanks to the campaign, which came in the wake of years of political upheaval. That same year, he took majority control of OBM.

In 1966, the rebranded Ogilvy & Mather International became the first ad agency to go public on both the New York and London Stock Exchanges. The company had 30 offices in 14 countries.

Seven years later, Ogilvy retired as Chairman of the company and moved to France. Though he was no longer involved in day-to-day operations, he remained in contact with the company. In fact, his correspondence was so vast that the local post office had to be upgraded to handle all the letters.

In 1981, he sent this memo to his agency partners:

Will Any Agency Hire This Man?

He is 38, and unemployed. He dropped out of college.

He has been a cook, a salesman, a diplomatist and a farmer.

He knows nothing about marketing and had never written any copy.

He professes to be interested in advertising as a career (at the age of 38!) and is ready to go to work for $5,000 a year.

I doubt if any American agency will hire him.

However, a London agency did hire him. Three years later he became the most famous copywriter in the world, and in due course built the tenth biggest agency in the world.

The moral: it sometimes pays an agency to be imaginative and unorthodox in hiring.

Even in retirement, he continued to change the direction of the agency.

That same decade, he briefly came out of retirement to run Ogilvy & Mather in India, as well as in Germany.

WPP commenced a hostile takeover of the Ogilvy Group in 1989, effectively making the firm the largest marketing communications company in the world. Ogilvy was named the company’s non-executive chairman, a position he held until 1992. Initially, he despised Sir Martin Sorrell, WPP’s founder, but later the two struck a close friendship. “When he tried to take over our company, I would liked to have killed him. But it was not legal. I wish I had known him 40 years ago. I like him enormously now,” Ogilvy said, only half joking.

David Ogilvy died on July 21st, 1999. He was 88 years old.

Still, he continues to have a tremendous impact on the advertising industry, thanks to the four elements that defined his work: emphasis on the ‘Big Idea’, achieving professional discipline, valuing the importance of research, and delivering actual results for his clients.

Elements, I think, we should all take to heart.